India’s agricultural landscape is undergoing a quiet but critical transformation, one that demands a closer look at how technology reaches its 70% rural population—particularly the marginal and small farmers who form the backbone of its food security. For decades, agricultural extension services have served as the bridge between research labs and farmlands, yet gaps persist in ensuring that innovations align with the realities of resource-poor farmers. Dr. Banarsi Lal, Chief Scientist and Head of Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) in Reasi, SKUAST-Jammu, highlights a systemic challenge: technologies often fail to account for the diverse farming systems across regions, leading to low adoption rates among those who need them most.

The issue isn’t just about developing better seeds or tools—it’s about rethinking how these solutions are designed and delivered. Traditional extension models, described as “push-type,” have historically prioritized top-down dissemination, where technologies are transferred to farmers without adequate consideration of local conditions. This approach, Dr. Lal notes, has proven ineffective for smallholders whose farming systems—shaped by ecological, economic, and social factors—demand tailored interventions. Instead, there’s a growing call for *location-specific*, *ecologically sustainable*, and *economically viable* technologies that emerge from a deeper understanding of farmers’ needs. Methods like Farming Systems Research and Extension (FSRE) and Technology Assessment and Refinement (TAR) through institution-village linkages are steps in this direction, but their scaling remains uneven.

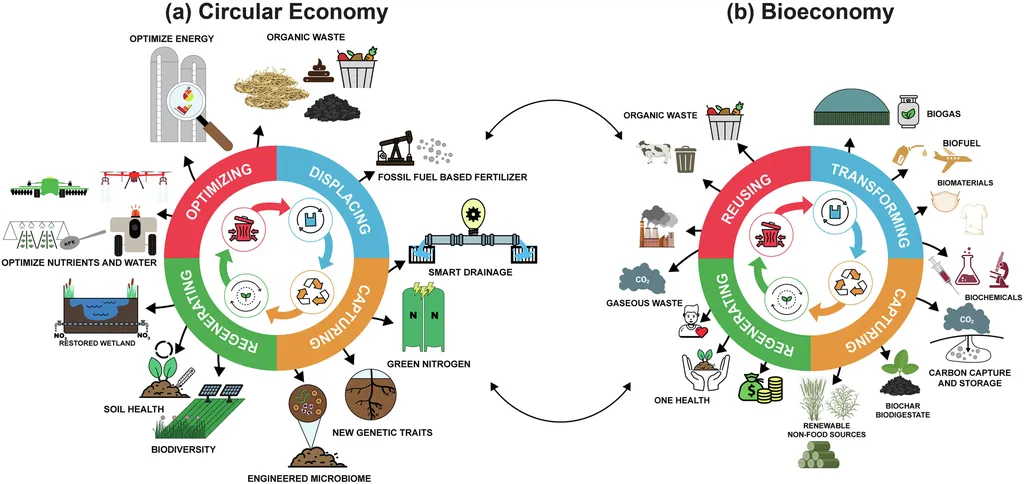

Agricultural extension in India isn’t a monolith; it’s a fragmented ecosystem involving government agencies, research centers, NGOs, private companies, and cooperatives. While this diversity offers multiple touchpoints for farmers, it also creates coordination challenges. The weaker the linkages between research, extension, and farmers, the higher the risk of technologies gathering dust on shelves. Studies confirm that these connections are often tenuous, with extension workers struggling to translate research into actionable insights for farmers. Strengthening these bonds requires institutional mechanisms that foster regular interaction—such as participatory trials on farmers’ fields—and a shift toward *circular models* of technology transfer, where feedback from farmers directly informs research. Unlike the linear “transfer of technology” (TOT) model, which treats farmers as passive recipients, circular models emphasize adaptive research and two-way communication, making space for innovation to flow in both directions.

Yet, even the most well-designed systems can falter if they overlook half the agricultural workforce: women. With nearly 80% of economically active rural women engaged in agriculture—compared to 63% of men—their exclusion from extension services is a glaring oversight. Dr. Lal points to cultural and structural barriers, from male-dominated extension teams to a lack of gender-sensitive technologies, which limit women’s access to critical information. Addressing this requires intentional efforts, such as training female extension workers, designing tools that account for women’s roles in farming and livestock management, and ensuring their participation in decision-making processes. The global consensus is clear: rural development cannot be achieved without integrating women as both beneficiaries and leaders of technological change.

The path forward, as Dr. Lal suggests, lies in redefining agricultural extension to meet modern challenges. This includes clarifying the objectives of extension programs, forging stronger ties with research institutions, financial bodies, and markets, and investing in well-trained, motivated staff. Privatization of extension services could play a role, but it must be strategically deployed—identifying which farmers and regions would benefit most from private-sector engagement while preserving public and cooperative efforts for marginalized groups. Currently, extension systems often focus on “contact farmers,” leaving resource-poor farmers on the periphery. A more inclusive approach would involve representatives from all farmer categories, ensuring that technologies are developed *with* them, not just *for* them.

At its core, the debate isn’t just about improving yields or adopting new tools; it’s about building a system where rural communities can *learn, adapt, and innovate* in ways that resonate with their lived experiences. Science and technology can indeed empower farmers, but only if the processes of development and dissemination are as dynamic as the farming systems they aim to serve. The question now is whether India’s agricultural extension can evolve from a one-size-fits-all model to one that embraces complexity—where farmers are not just recipients of technology, but active partners in shaping it.