In the heart of South Africa’s protected areas, a treasure trove of botanical data is being unlocked, promising to revolutionize conservation efforts and even offer significant benefits to the agriculture sector. Researchers, led by Nikisha Singh from South African National Parks (SANParks) and the University of the Free State, are harnessing the power of herbarium collections and data digitization to paint a clearer picture of the country’s biodiversity.

Herbarium collections, often overlooked, are repositories of pressed plants collected over centuries. These collections are more than just historical artifacts; they are rich sources of data that can inform present-day conservation strategies and agricultural practices. “These collections are a goldmine of information,” Singh explains. “They provide a historical baseline of plant distributions, which is crucial for understanding changes in biodiversity over time.”

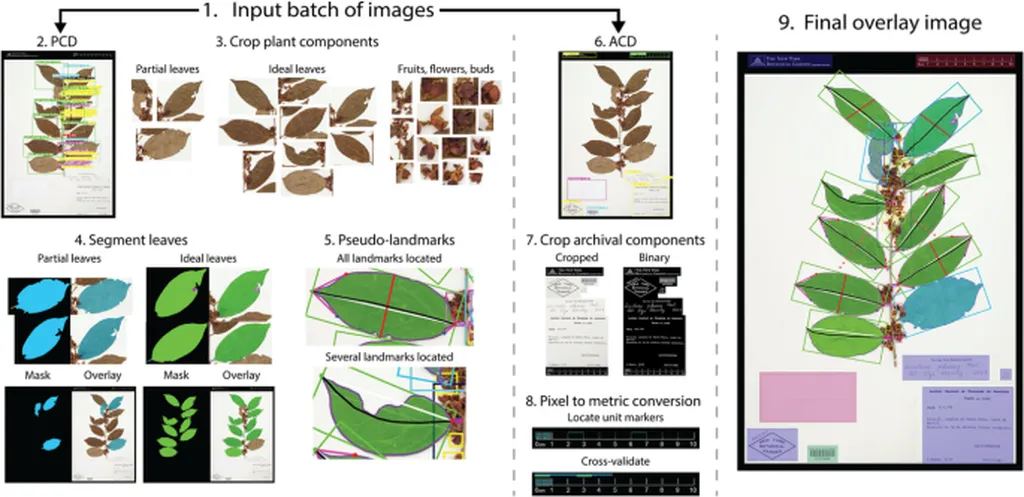

The research, published in ‘Koedoe: African Protected Area Conservation and Science’, focuses on the plant records within South African National Parks. By digitizing these records, the team has made this invaluable data accessible to a global audience. This digitization effort is not just about preserving the past; it’s about informing the future. For instance, understanding the historical distribution of plant species can help predict how they might respond to climate change, a critical factor for both conservationists and farmers.

The implications for the agriculture sector are substantial. Farmers can use this data to make informed decisions about crop selection, rotation, and pest management. “By understanding the natural distribution and behavior of plant species, we can better predict potential crop pests and diseases,” Singh notes. This proactive approach can lead to more sustainable and productive farming practices, ultimately benefiting the entire agricultural value chain.

Moreover, the data can aid in the development of more resilient crop varieties. By studying the traits of wild relatives of cultivated plants, researchers can identify genes that confer resistance to drought, pests, or diseases. This information can then be used to breed more robust crop varieties, a boon for farmers facing increasingly unpredictable growing conditions.

The research also underscores the importance of protected areas as living laboratories. “Protected areas are not just for conservation,” Singh emphasizes. “They are also invaluable for research and education. The data from these areas can drive innovation in various sectors, including agriculture.”

As we grapple with the challenges of climate change and food security, the insights gleaned from South Africa’s herbarium collections offer a beacon of hope. They remind us that the answers to some of our most pressing problems may lie in the past, waiting to be discovered and applied in innovative ways. With continued investment in data digitization and research, we can unlock even more potential from these invaluable collections, shaping a more sustainable and productive future for all.