In the heart of Southeast Asia, a silent transformation is underway, one that could reshape our understanding of carbon emissions and the agricultural landscape. A recent study published in *AGU Advances* has shed light on the intricate dance between land use change, drought, and greenhouse gas emissions from tropical peatlands, offering insights that could steer future agricultural practices and climate policies.

The research, led by Takashi Hirano from the Research Faculty of Agriculture at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan, delves into the complex interplay of factors influencing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from peatlands. These emissions, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane, are significantly impacted by groundwater levels (GWL), which are in turn affected by drainage and droughts, particularly during El Niño events.

The study reveals that peat forests, even when undrained, are a net source of CO2-equivalent GHGs. However, the situation worsens when forests are drained or converted to managed peatlands. “Decadal mean annual GHG emission rates increase 2.8-fold when forests are drained and 6.4-fold when undrained forests are converted to managed peatlands,” Hirano explains. This finding underscores the profound impact of land use change on carbon emissions, a critical consideration for the agriculture sector.

Droughts, too, play a significant role. The study found that droughts increase total annual GHG emissions by 16% across the study area. This is particularly relevant given the increasing frequency and severity of droughts due to climate change. “Droughts significantly lower the GWL, the main environmental factor that controls GHG emissions in peatlands,” Hirano notes.

The study also offers a glimmer of hope. Climate models project an increase in precipitation in the mid-21st century, which could lead to higher GWL and a consequent reduction in peat decomposition. This could potentially mitigate some of the GHG emissions from these regions.

The implications for the agriculture sector are substantial. As the world grapples with the need to increase food production while reducing carbon emissions, understanding the GHG dynamics of peatlands becomes crucial. The study’s findings could guide more sustainable land use practices, helping to balance the need for agricultural expansion with the imperative to reduce carbon emissions.

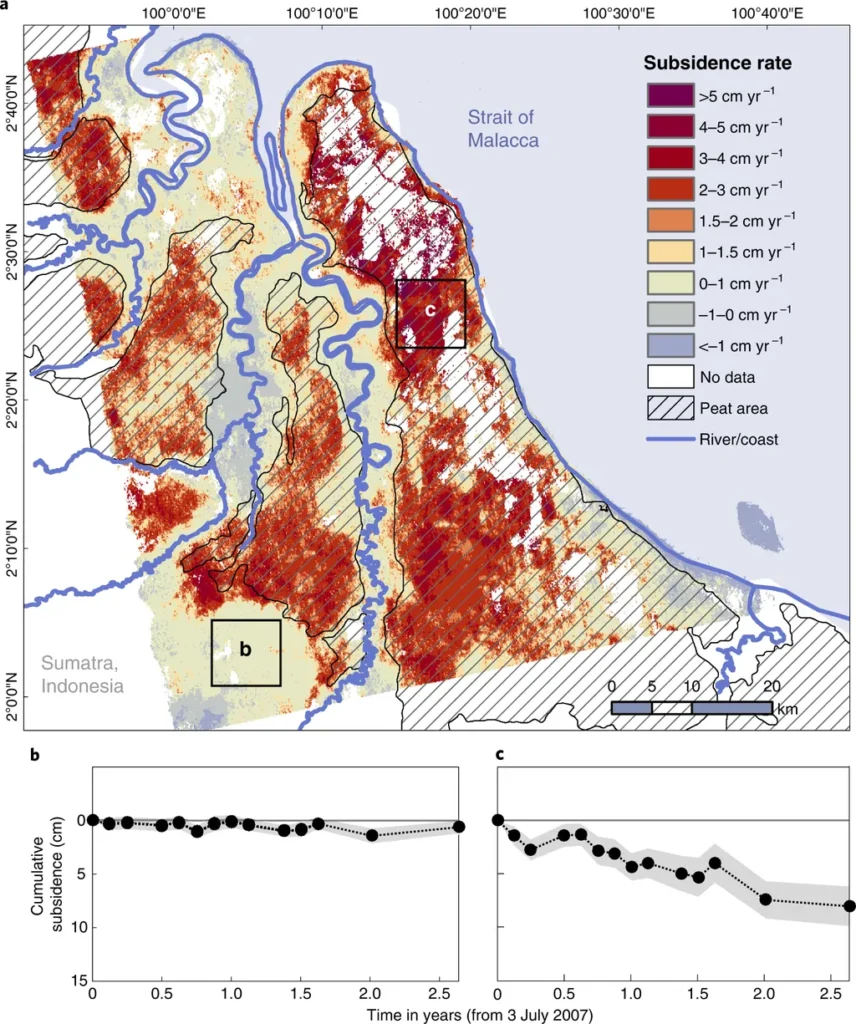

Moreover, the study’s innovative method of estimating spatiotemporal GWL variation from satellite-derived antecedent precipitation could revolutionize how we monitor and manage peatlands. This method could be applied globally, providing valuable data for climate models and informing policy decisions.

As we look to the future, this research could shape the development of more accurate emission factors that account for spatiotemporal variations in GWL. It could also pave the way for more sophisticated models that incorporate CO2 uptake through photosynthesis, further reducing uncertainty in our estimates of GHG emissions.

In the end, this study is a testament to the power of scientific inquiry to illuminate the complex interactions between land use, climate, and carbon emissions. As we strive to build a more sustainable future, such insights will be invaluable, guiding us towards practices that nourish both our planet and its people.