In the heart of Tunisia’s semi-arid region, a groundbreaking study is reshaping how we monitor and manage soil salinity, a critical factor in agricultural productivity. Researchers, led by Dorsaf Allagui from the National Research Institute of Rural Engineering, Water and Forests, have combined two frequency domain electromagnetic induction (FD-EMI) sensors, EM31 and EM38, to create a more comprehensive picture of soil salinity distribution. Their work, published in the journal ‘Land’, offers promising insights for the agriculture sector, particularly in areas reliant on brackish water irrigation.

Soil salinity is a silent menace to crops and groundwater quality. Excessive salt accumulation in the root zone can stifle plant growth and reduce soil fertility. Traditional methods of monitoring soil salinity involve labor-intensive soil sampling and laboratory analysis, providing only point-scale measurements. However, the new study leverages the power of geophysical survey design and inverse modeling to offer a more extensive assessment of soil conditions.

The researchers used multiple measurement heights and coil orientations to enhance depth sensitivity, thereby improving salinity predictions. “We combined two FD-EMI mono-channel sensors and operated them at different heights and with different coil orientations,” Allagui explained. “This multi-configuration approach allowed us to derive soil salinity information via inverse modeling with a laterally constrained inversion (LCI) approach.”

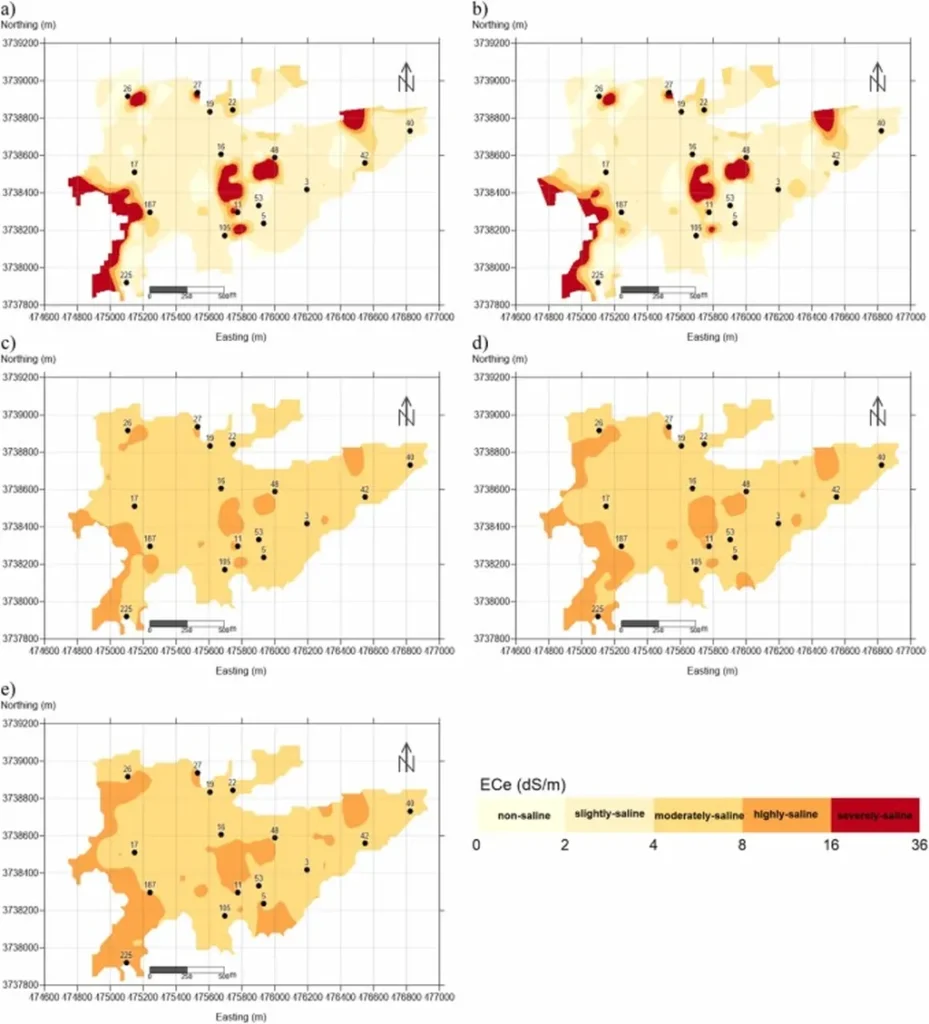

The results were striking. The study revealed the vertical distribution of soil salinity in relation to different irrigation systems, both in the short and long term. The expected transfer of salinity from the surface to deeper layers was systematically observed. However, the intensity and spatial distribution of soil salinity varied between different crops, depending on the frequency and amount of drip or sprinkler irrigation. The study also found that vertical salinity transfer is influenced by the wet or dry season.

The commercial implications for the agriculture sector are significant. By providing a more detailed representation of soil salinity distribution across spatial and temporal scales, this method can help farmers make informed decisions about irrigation and leaching rates. This can lead to improved soil fertility and crop production, ultimately enhancing the sustainability of irrigated agricultural production.

The study also highlights the potential of combining different FD-EMI sensors for monitoring soil salinity. This could pave the way for more sophisticated and accurate soil monitoring systems in the future. As Allagui noted, “The inversion approach provides a more extensive assessment of soil conditions at depths up to 4 m with different irrigation systems.”

This research is a testament to the power of innovative technologies in addressing longstanding agricultural challenges. As we face increasing pressures on water resources and the need for sustainable food production, such advancements become ever more critical. The study not only contributes to our understanding of soil salinity dynamics but also opens up new avenues for improving agricultural practices and ensuring food security.

In the quest for sustainable agriculture, every breakthrough counts. This study, with its novel approach to soil salinity monitoring, is a significant step forward. As the agriculture sector continues to evolve, such innovations will be key to shaping a more resilient and productive future.