In the vast, high-altitude expanses of the Tibetan Plateau, a silent battle for survival is unfolding beneath our feet. As salinity levels fluctuate across alpine wetlands, the microscopic inhabitants of the soil—bacteria and archaea—are responding in strikingly different ways. A recent study published in *Fundamental Research* sheds light on these contrasting strategies, offering insights that could reshape our approach to soil conservation and agricultural resilience.

The research, led by Xu Liu of the State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, reveals that as salinity increases, bacterial diversity declines in a predictable, linear fashion. However, archaea tell a different story. Their diversity initially drops but then rebounds, suggesting a more complex adaptation to salt stress. This divergence isn’t just academic; it has real-world implications for how we manage and conserve soil ecosystems, particularly in agriculture.

“Bacteria seem to be enhancing their positive interactions under stress, almost like forming alliances to survive,” Liu explains. “Archaea, on the other hand, appear to rely more on individual stress tolerance, with their communities shifting toward salt-loving species.” This finding aligns with the Stress-Gradient Hypothesis, which posits that environmental stress can alter the balance between competition and cooperation in ecological networks.

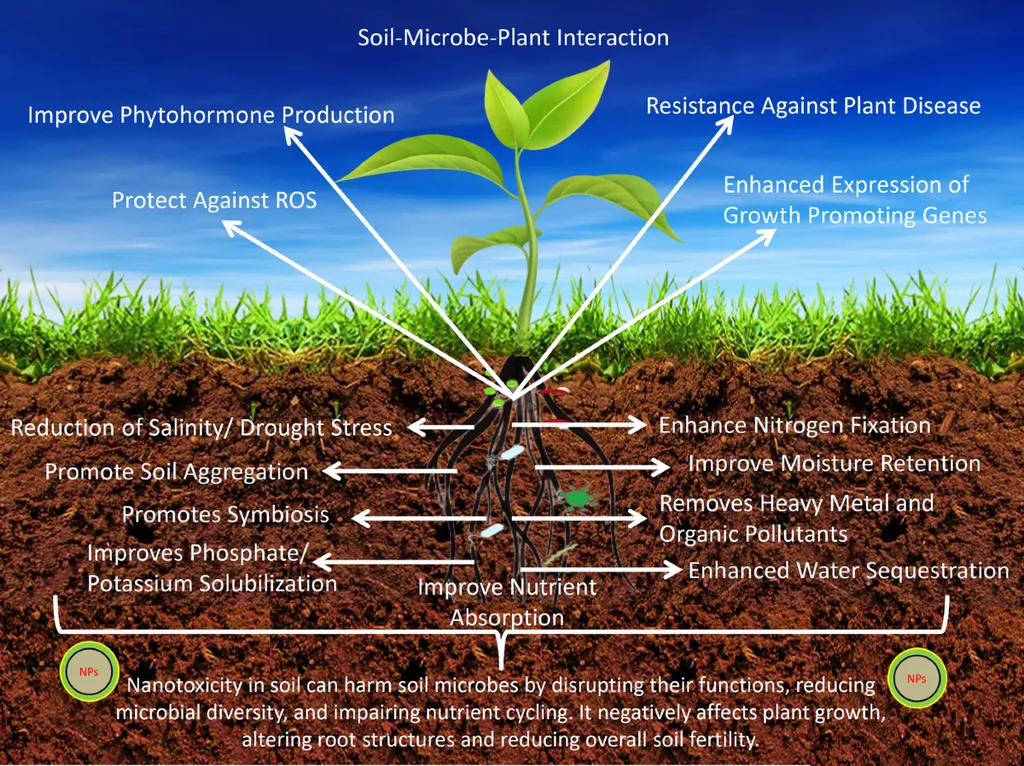

For the agriculture sector, these insights could be game-changing. Understanding how microbial communities respond to salinity could lead to more resilient crop systems, particularly in regions prone to soil salinization—a growing concern as climate change intensifies. By leveraging the natural strategies of bacteria and archaea, farmers might be able to cultivate more robust soil microbiomes that enhance plant health and productivity, even in challenging conditions.

The study also highlights the importance of ecological networks in maintaining biodiversity. Network analysis showed that bacteria form more complex positive associations under salt stress, suggesting that cooperation is key to their survival. Archaea, however, exhibit a decline in both positive and negative interactions, indicating a shift toward stress-tolerant species. This duality could inform future conservation efforts, ensuring that soil management practices account for the unique needs of different microbial communities.

As we face a future of increasing environmental stress, research like this is more critical than ever. By unraveling the intricate web of microbial life in our soils, we can develop strategies that not only conserve biodiversity but also bolster agricultural productivity. The findings from the Tibetan Plateau offer a blueprint for how we might adapt to a changing world, one microorganism at a time.