In the heart of every agricultural innovation lies a quest to understand the intricate dance of nature’s mechanisms. A recent study published in the journal ‘Plants’ has unveiled a fascinating phenomenon that could reshape our understanding of plant physiology and open new avenues for drought-resistant crop development. Led by Yangfan Chai from the College of Biosystems Engineering and Food Science at Zhejiang University, the research delves into the enigmatic world of reverse sap flow in watermelon plants, offering insights that could revolutionize agricultural practices.

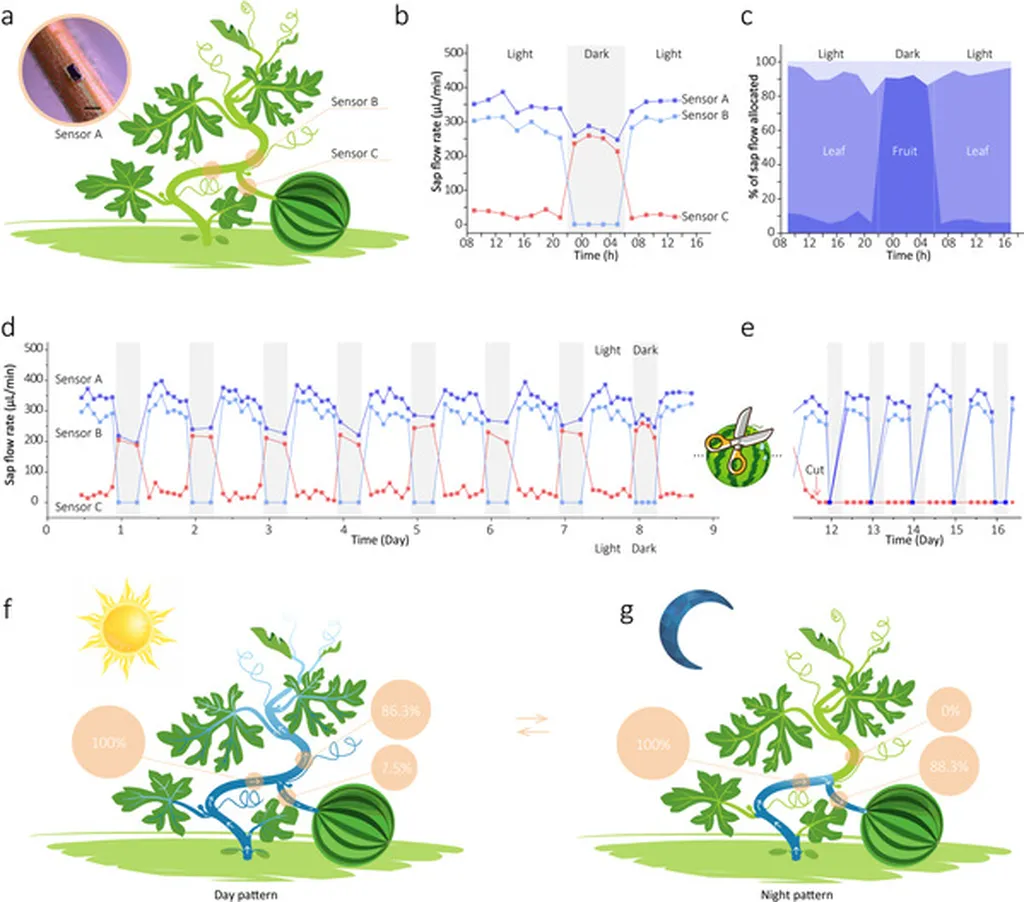

Traditionally, sap flow is understood as the upward movement of water and nutrients from roots to the rest of the plant, including fruits, which are often seen as mere “sinks” in the source–sink theory. However, Chai’s team has discovered that this one-way street might not be as straightforward as previously thought. By integrating real-time sap flow measurements with environmental monitoring, the researchers identified that fruits can also act as sources, sending sap back to other parts of the plant under certain conditions.

The study reveals that reverse sap flow is triggered by a water supply–consumption imbalance within the plant, exacerbated by rapid changes in light intensity and soil drought. “We found that when plants experience sudden surges in light intensity or prolonged drought, the fruit starts to contribute to the plant’s water redistribution,” explains Chai. This finding challenges the conventional source–sink theory and introduces a new dimension to our understanding of plant water management.

The implications for the agriculture sector are profound. As climate change continues to pose challenges like increased drought frequency and intensity, understanding and harnessing reverse sap flow could be a game-changer. By breeding or engineering crops that can efficiently utilize this mechanism, farmers might be able to grow more resilient plants that can better withstand water scarcity.

Moreover, the innovative use of plant-wearable sensors in this research paves the way for more sophisticated monitoring tools. These sensors, which provide real-time data on sap flow and environmental conditions, could become a staple in precision agriculture, enabling farmers to make data-driven decisions and optimize water usage.

Looking ahead, this research could inspire further studies into the physiological responses of other crops to environmental stressors. It also opens the door to exploring how reverse sap flow might be manipulated to improve crop yield and quality. As Chai puts it, “This is just the beginning. There’s so much more to uncover about how plants adapt to their environment, and each discovery brings us one step closer to sustainable agriculture.”

In an era where food security is a growing concern, such breakthroughs are not just academic exercises but vital steps towards securing our future. The study by Chai and his team is a testament to the power of interdisciplinary research, combining plant science, engineering, and environmental monitoring to tackle real-world problems. As we continue to unravel the complexities of plant life, we edge closer to a future where agriculture is not just about feeding the world but doing so sustainably and resiliently.