In the intricate world of plant microbiomes, a new study has shed light on the complex interplay between peas (Pisum sativum L.) and their fungal communities, offering insights that could reshape agricultural practices and crop management strategies. Published in the Journal of Integrative Agriculture, the research led by Yu Wang from Ningbo University, China, delves into the ecological effects of host niches and genotypes on the diversity and composition of fungal communities associated with peas.

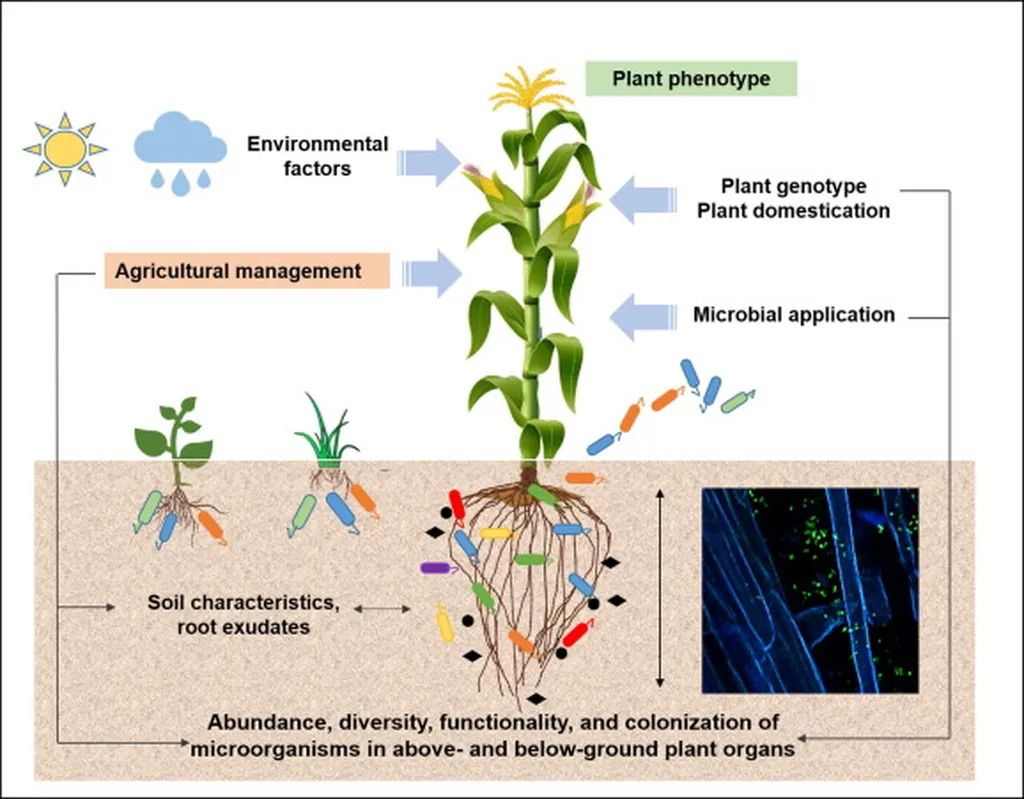

Fungi are indispensable allies in the plant kingdom, aiding in nutrient acquisition, promoting growth, and bolstering resistance to both environmental stresses and pathogens. Yet, despite their importance, the fungal communities associated with peas have remained relatively understudied. This new research aims to fill that gap, employing a multi-level approach that includes pattern recognition, mechanism validation, and dynamic tracking methods.

The study reveals that the dominant fungal phyla across various pea niches and genotypes are Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mortierellomycota. Notably, the community structures of the soil–plant continuum were found to be primarily determined by the pea niches rather than the genotypes. “This indicates a strong niche specificity and microbial replacement across microhabitats,” explains Wang, highlighting the significance of the environment in shaping fungal communities.

One of the key findings of the study is that β-diversity decomposition—essentially the variation in species composition between different habitats—was largely attributed to species replacement rather than differences in richness. This suggests that different microhabitats within the pea plant favor different fungal species, leading to a dynamic and diverse fungal community.

The research also employed a neutral model analysis to understand the processes driving community assembly. The results showed that stochastic processes, or random events, influenced genotype-associated communities, while deterministic processes, such as environmental filtering and species interactions, played a dominant role in niche-based community assembly. This dual-process understanding could be crucial for developing targeted strategies to manipulate fungal communities for agricultural benefits.

Source-tracking analysis identified niche-to-niche fungal migration, with key genera such as Erysiphe, Fusarium, Cephaliophora, Ascobolus, Alternaria, and Aspergillus playing significant roles. The study found that migration rates from exogenous to endogenous niches were relatively low, suggesting that the pea epidermis acts as a selective barrier. “This barrier filters and enriches microbial communities prior to internal colonization,” Wang notes, emphasizing the plant’s role in shaping its internal microbiome.

The commercial implications of this research are substantial. Understanding the assembly rules of the pea-associated fungal microbiome can lead to more effective crop management practices. For instance, farmers could potentially enhance beneficial fungal communities to improve nutrient uptake, increase resilience to stresses, and reduce the incidence of diseases. This could translate into higher yields and more sustainable agricultural practices.

Moreover, the insights gained from this study could be applied to other crop plants, paving the way for a more holistic approach to plant health and productivity. As the agricultural sector continues to face challenges from climate change and increasing demand for sustainable practices, such research becomes increasingly valuable.

In the broader context, this study underscores the importance of understanding the complex interactions between plants and their microbial communities. As Yu Wang and colleagues continue to unravel these intricate relationships, the potential for innovative agricultural technologies and practices grows ever more promising. The future of agriculture may well lie in our ability to harness the power of these tiny, yet mighty, fungal allies.