In the face of escalating climate challenges and the pressing need for sustainable agricultural practices, a groundbreaking review published in the *Turkish Journal of Agriculture: Food Science and Technology* offers a compelling roadmap for leveraging soil microbiome engineering to bolster global food security. Led by Abdur Rahman Al Mamun of Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University in Bangladesh, the research synthesizes recent advancements in microbial biotechnology, highlighting both the promise and the hurdles of this emerging field.

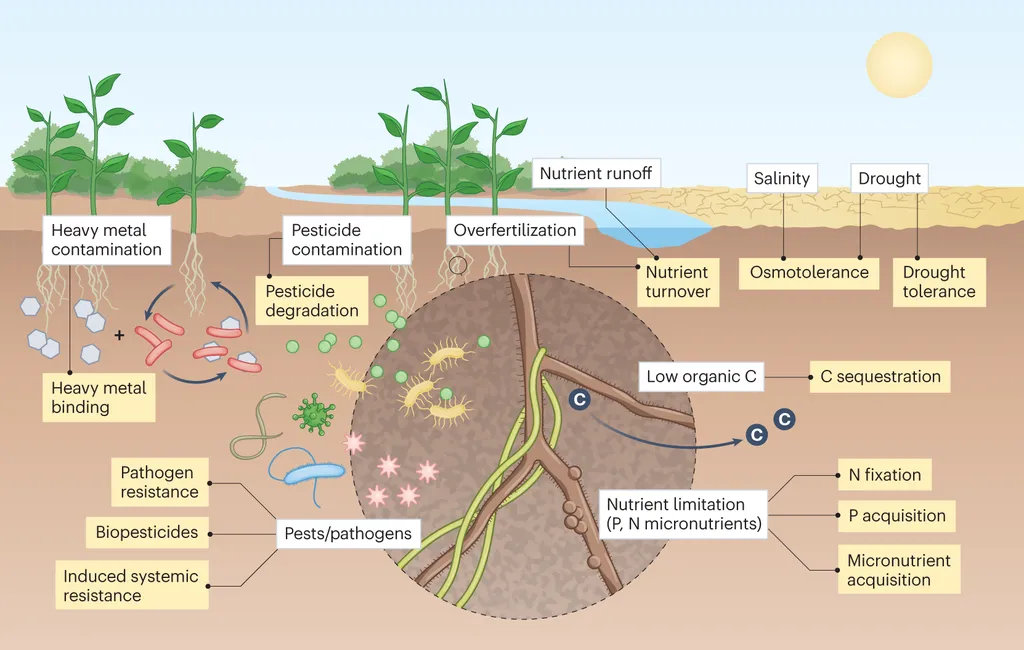

Soil microbiome engineering involves the deliberate manipulation of microbial communities to enhance soil health, crop resilience, and agricultural productivity. By deploying advanced biofertilizers, synthetic microbial communities (SynComs), and genetic tools, scientists aim to create climate-resilient agroecosystems. However, as Al Mamun and his co-authors point out, the path from lab to field is fraught with challenges. “The current reliance on short-term, single-stress inoculation studies limits our understanding of long-term ecological stability,” Al Mamun explains. “We need multi-year studies that capture the dynamic interactions within soil microbiomes under real-world conditions.”

One of the key obstacles identified in the review is the lack of standardized application protocols and harmonized regulatory frameworks. Without these, achieving reproducible success and streamlining commercialization becomes a daunting task. The authors argue that the absence of clear guidelines not only hampers technological progress but also delays the adoption of these innovations by farmers. “Standardization is crucial for scaling up these technologies,” says Al Mamun. “It ensures consistency and builds trust among stakeholders, from researchers to policymakers and farmers.”

Beyond technological and ecological challenges, the review underscores the importance of addressing socio-economic barriers. Farmer adoption behavior and equitable access to these technologies in resource-scarce regions are critical factors that cannot be overlooked. The authors propose a three-scale research–policy–practice framework to bridge these gaps, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration. “We need to integrate biotechnology, ecology, and social science to create a holistic approach,” Al Mamun notes. “This will ensure that the benefits of soil microbiome engineering are accessible to all, particularly those in vulnerable regions.”

The commercial implications of this research are substantial. As the agricultural sector grapples with the impacts of climate change, the development of climate-resilient crops and sustainable farming practices could revolutionize the industry. By engineering soil microbiomes, farmers could reduce their dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, leading to cost savings and environmental benefits. Moreover, the potential for enhanced crop yields and improved soil health could drive significant economic growth in the agritech sector.

Looking ahead, the review calls for a paradigm shift in how we approach soil microbiome engineering. By adopting a holistic, interdisciplinary approach, researchers and policymakers can pave the way for equitable scaling of these technologies. As Al Mamun and his colleagues argue, the soil is not just a medium for growth but an engineered living system that holds the key to achieving global food security and climate adaptation goals.

In the quest for sustainable agriculture, soil microbiome engineering stands out as a promising frontier. With continued research, standardized protocols, and inclusive policies, this innovative field could reshape the future of farming, ensuring a more resilient and equitable food system for generations to come.