In the vast expanse of space, where human life teeters on the edge of survival, an unlikely ally may hold the key to sustaining life beyond Earth: biofilms. These complex communities of microorganisms, often maligned on our home planet for their role in infections and infrastructure damage, are now being recognized for their potential to support life in the harsh environment of space. A recent review published in *npj Biofilms and Microbiomes* sheds light on the adaptability of biofilms in space and their crucial roles in human and plant health, offering a glimpse into a future where these microbial communities could underpin life support systems for astronauts and space-based agriculture.

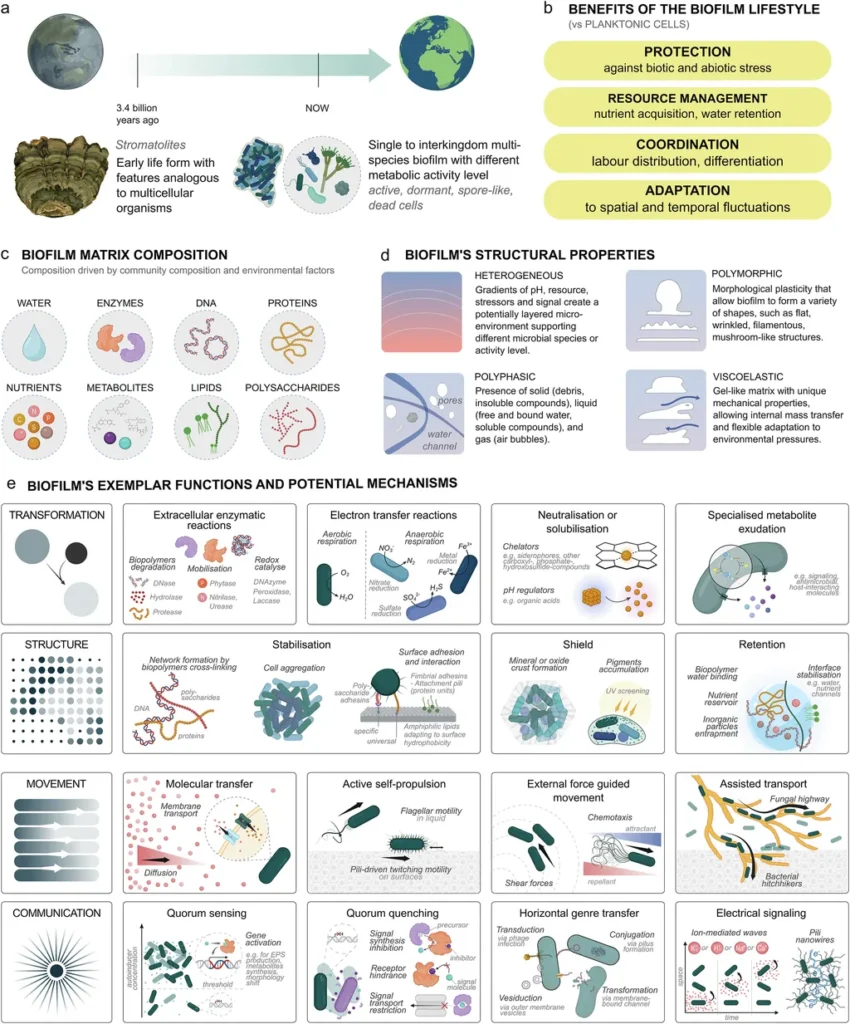

Biofilms, which form when microorganisms adhere to surfaces and grow in structured communities, are ubiquitous in natural and engineered systems. On Earth, they play essential roles in nutrient cycling, waste degradation, and even human health, where they can form protective layers on our skin and in our guts. In space, however, their potential has remained largely unexplored beyond concerns about their role in contamination and disease. The review, led by Katherine J. Baxter of the School of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Glasgow, challenges this narrow perspective, highlighting the adaptability of biofilms to spaceflight stressors and their potential to support life in extreme environments.

“Biofilms have evolved over billions of years to thrive in diverse and often harsh conditions,” Baxter explains. “Their ability to adapt to the unique challenges of spaceflight—such as microgravity, radiation, and nutrient limitations—makes them a promising candidate for supporting human and plant life in space.”

One of the most promising applications of biofilms in space is their role in life support systems. Biofilms can be engineered to break down waste products, recycle nutrients, and even produce oxygen, all of which are critical for sustaining life in the confined and resource-limited environment of a spacecraft or space station. For example, certain biofilms can convert carbon dioxide into oxygen through photosynthesis, mimicking the role of plants in Earth’s ecosystems. This capability could be harnessed to supplement or even replace traditional life support systems, reducing the need for resupply missions and increasing the sustainability of long-duration space exploration.

In the agriculture sector, biofilms could revolutionize space-based farming. Plants grown in space face numerous challenges, including reduced gravity, altered light conditions, and limited access to nutrients. Biofilms could help mitigate these challenges by enhancing nutrient availability, protecting plant roots from pathogens, and even improving water retention in soil. “By leveraging the natural abilities of biofilms, we can create more resilient and productive agricultural systems in space,” Baxter notes. This could pave the way for sustainable food production on the Moon, Mars, and beyond, supporting the long-term goals of space colonization and interplanetary travel.

The adaptability of biofilms to space environments also raises intriguing questions about their role in the origins of life. Some scientists speculate that biofilms may have played a crucial role in the emergence of life on Earth, providing a protected environment for early microorganisms to thrive. If biofilms can adapt to the extreme conditions of space, it is possible that they could also facilitate the emergence of life on other planets or moons, opening up new avenues for astrobiological research.

As we look to the future, the potential applications of biofilms in space are vast and varied. From supporting human life to revolutionizing space-based agriculture, these microbial communities could play a pivotal role in our journey to the stars. The review by Baxter and her colleagues not only highlights the adaptability of biofilms to spaceflight stressors but also underscores the need for further research into their beneficial roles. By harnessing the power of biofilms, we may unlock new possibilities for sustaining life beyond Earth and expanding the boundaries of human exploration.

Published in *npj Biofilms and Microbiomes*, the review was led by Katherine J. Baxter of the School of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Glasgow.