In the vast, salty expanses of the world’s most inhospitable environments, a hidden world of microorganisms thrives. These halophilic and halotolerant microbes have evolved unique adaptations to survive and even flourish in high-salt conditions. Now, a new editorial published in *Frontiers in Microbiology* is shedding light on the potential applications of these remarkable organisms, with significant implications for the agriculture sector.

The editorial, led by Rosa María Martínez-Espinosa from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Edaphology and Agricultural Chemistry at the University of Alicante, Spain, explores the latest research on these salt-loving microbes. It delves into their mechanisms of adaptation, their roles in saline environments, and their potential uses in agriculture.

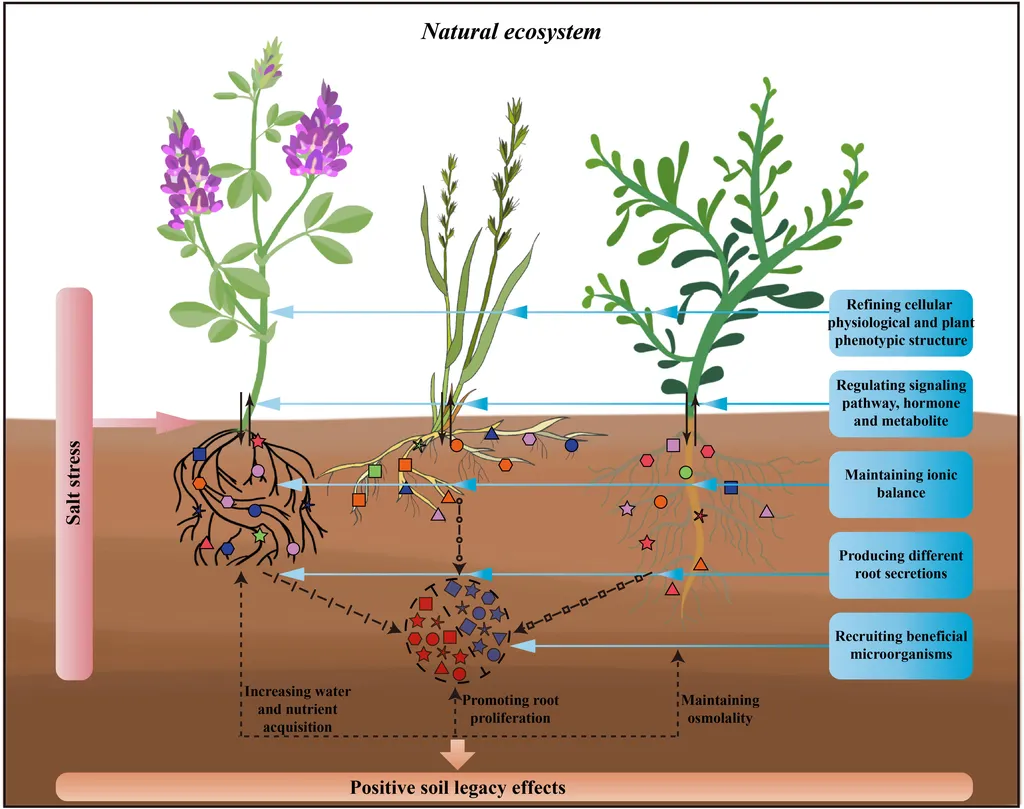

One of the most promising areas of research is the use of halophilic and halotolerant microorganisms to improve crop production in saline soils. “These microbes can help plants cope with salt stress, enhancing their growth and productivity,” Martínez-Espinosa explains. This could be a game-changer for farmers grappling with soil salinization, a growing problem exacerbated by climate change and poor irrigation practices.

The commercial impacts of this research could be substantial. By harnessing the power of these microbes, farmers could potentially grow crops in areas previously deemed unsuitable, opening up new opportunities for agriculture. Moreover, these microorganisms could be used to develop biofertilizers and biostimulants, providing a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to traditional chemical inputs.

But the potential applications don’t stop there. Halophilic and halotolerant microorganisms also hold promise for bioremediation, the use of living organisms to clean up environmental pollution. They could be employed to treat saline wastewater, for instance, or to remediate soils contaminated with heavy metals.

The research also offers insights into the fundamental biology of these organisms, which could pave the way for future developments. “Understanding how these microbes adapt to high-salt environments can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of stress tolerance in general,” Martínez-Espinosa notes. This knowledge could be applied to other areas of research, from human health to industrial biotechnology.

As the world grapples with the challenges of climate change and food security, the work of Martínez-Espinosa and her colleagues offers a glimmer of hope. By unlocking the secrets of these remarkable microorganisms, we may be able to develop innovative solutions to some of our most pressing problems. The future of agriculture, it seems, may lie in the salty soils and waters where these halophilic and halotolerant microbes thrive.